“Data-Driven Thinking” is written by members of the media community and contains fresh ideas on the digital revolution in media.

Today’s column is written by Joshua Koran, head of innovation labs at Zeta Global.

How would you feel if a proverbial Big Brother controlled all data access and processing on the web? There are certain internet gatekeepers – see: operating systems, app stores and browsers – that insist they alone should be trusted with such control.

They assert they can preemptively protect the rest of us from potential data-related harms, a bit like Minority Report precogs. This dystopian perspective posits that it’s okay to punish others today for harm they may commit in the future.

The truth is, any technology – from a hammer to an iPhone – can be abused by a bad actor.

That doesn’t mean we outlaw hammers, nor should we empower internet gatekeepers to control who gets access to data and who doesn’t. While police states deny people freedom for a promised reduction in crime, that seems like an undesirable outcome for the web.

Funding the open web

Whether you favor online centralization or decentralization, someone needs to pay for the content and services you access.

The original internet was operated by pay-to-access gatekeepers, such as Prodigy, CompuServe and AOL, that controlled access to almost all online content and services.

Unfortunately, not everyone could afford access. When the open web came along to reduce barriers to access, more people began enjoying what had previously been the privilege of the few. Decentralization inspired billions to participate, leading to a far wider diversity of content than previously imaginable.

Today’s ad-funded web isn’t without its costs. It requires the collection and processing of web activity, but in a manner by which marketers do not know who you are. Instead, pseudonymous identifiers that are not directly related to a specific person, allow publishers to optimize the user experience on their websites and marketers to control, measure, and optimize the advertising that funds these publishers.

The future of this decentralized model hinges on the threatened removal of cookies and mobile advertising identifiers, such as Apple’s IDFA.

So, the question is: Should we return to the centralized model of the past – or should we support the decentralized model of the present?

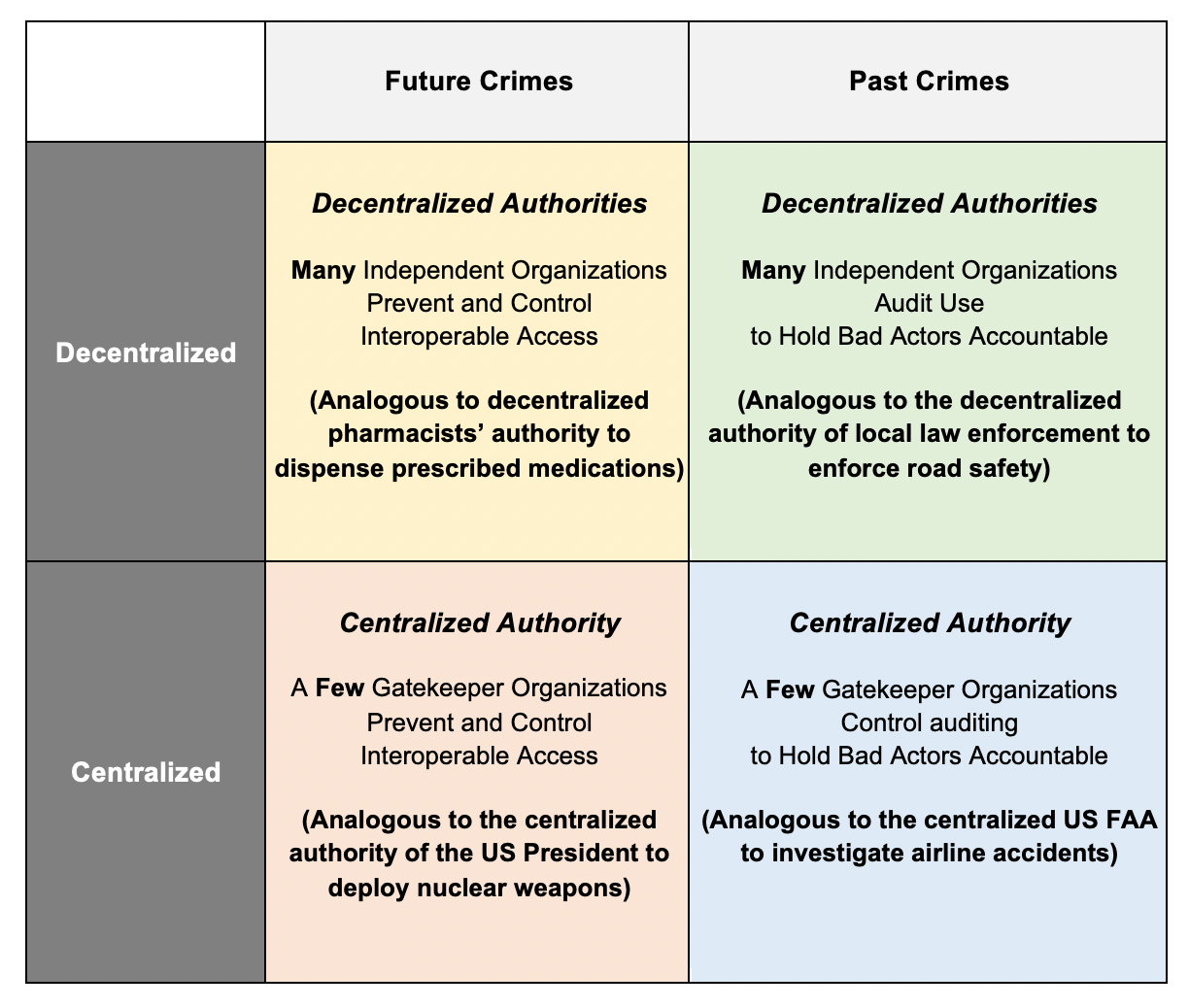

Four potential futures for the web

The four quadrants below explain how we can classify access to, and the use of, web technologies.

In which of these four quadrants would you place your web browser?

Your answer likely depends on the perceived level of risk. Different information comes with different levels of risk, depending on whether data is sensitive (for example, checking your financial assets with your bank account number) or non-sensitive (say, checking the weather online pseudonymously).

Future crimes: Decentralized authorities

Proponents of “future crimes thinking” assume that the mere existence of a pseudonymous identifier on a web-enabled device is a privacy risk. Thus, any organizations that create such identifiers must police their use.

To illustrate, consider the supply chain between a farmer and a restaurant. With “future crimes thinking,” if a restaurant were causing harm – for example, causing a diner to have food poisoning – the remedy would be for the farmer to stop sending apples to that restaurant.

Do you think the farmer should police all the restaurants that use its produce?

Such thinking comes with a laundry list of logistical nightmares for implementation and execution:

- How does an access ban compensate any of the diners harmed?

- How long would supply be disrupted before bankrupting the restaurant?

- Should the farmer create a private justice system to govern all restaurants relying on its apples?

The Trade Desk’s open-source Unified ID 2.0 prescribes how multiple “operators” can provision pseudonymous identifiers to help publishers work with their supply chain partners, suggesting these decentralized operators receive a “kill switch” over an organization’s continued access.

This transforms each operator into a police enforcement agent, which is hardly an appropriate remedy. Given The Trade Desk has donated this technology to the Partnership for Responsible Media, hopefully we can revisit this idea. After all, what trade body wants to burden its members with the costs of replicating each region’s justice system?

Future crimes thinking: Centralized authorities

Some internet gatekeepers believe pseudonymous identifiers pose such a high privacy risk that they must be policed by a centralized authority. That means centralizing the generation of the identifier and its processing. Yet such proponents are either redundantly acting alongside regulators or even worse writing brand new regulations for each country.

Given the impact on all web stakeholders, we would hope the rules that govern the web provide a level playing field, rather than self-preferencing a company’s own web services. (This is why regulators have labeled such anticompetitive actions as “privacy fixing” and are calling the motivations of these gatekeepers into question.)

Regardless of intent, policies should be judged by the outcomes they produce. All sides agree that removing interoperable data disproportionately impacts smaller organizations, as they must rely more on supply chain partners. We should not overlook such anticompetitive outcomes when evaluating the desirability of these policies.

Past crimes: Centralized authorities

Under the “past crimes” view, bad actors can only be punished after they violate a law. Using the farmer/restaurant example, officials audit a restaurant’s use of apples, rather than the mere possession of apples, to determine harm.

To equally enforce the law, a centralized agency requires a consistent definition of what activities constitute a violation. On the web, this means focusing on improving the accountability of data processing.

Easing the identification of bad actors in turn eases the ability to punish them. Thus, proponents of centralized policing advocate for more transparency via accountable audit logs, which are the digital equivalent of receipts.

Requiring a centralized authority to license the organizational identifiers that are sent in audit logs to a centralized clearing house is one example.

But, again, the drawbacks of centralization are many, including steep administrative costs, high enforcement costs and the quagmire of representing the interests of global stakeholders when creating governing regulations.

Past crimes: Decentralized authorities

Proponents of decentralization advocate reducing chokepoints of control by relying on existing public/private keys of HTTPS to generate non-repudiable organizational identifiers for accountable audit logs.

In this scenario, the entire supply chain involved in delivering content to a website is transparent to people, publishers and marketers, thereby ensuring that it’s easy to audit privacy violations. Moreover, it allows publishers to ensure their rule sets are honored and marketers to root out sources of publisher fraud.

And given the decentralization aspect, it provides these benefits with minimal costs.

The time is now

When harms are extreme, they deserve centralized control, but this control comes with a cost.

Are the potential harms on the open web great enough to warrant a restriction of social liberties and competition? The answer we collectively arrive at will determine the future of the web for generations to come.

The actions you take now will impact the governance of the web for everyone around the globe. Now is the time to make sure your voice is heard, so that the open web becomes what you want, not only for yourself now but also for the future.

Follow Zeta Global (@ZetaGlobal) and AdExchanger (@adexchanger) on Twitter.